In Moulmein, Burma, I was a young police officer, despised by the locals. It was the only time I felt significant enough to be hated. The Burmese resented Europeans, though they never rioted. Still, they’d spit betel juice on women in the market or trip me during football games, laughing as the crowd jeered. The young Buddhist priests were the worst, always mocking from street corners.

I despised my job and the British Empire. I saw its cruelty—filthy prison cells, scarred convicts, and a system that left me guilty. Secretly, I supported the Burmese, but I was stuck, hating both the Empire and the locals who made my life miserable.

One day, a call came about an elephant wrecking the bazaar. I grabbed a weak rifle and rode out. The elephant, a tame one gone “must,” had broken free, destroyed huts, killed a cow, and crushed a rubbish van. In a poor neighborhood, I found a dead coolie, his body mangled in the mud by the elephant.

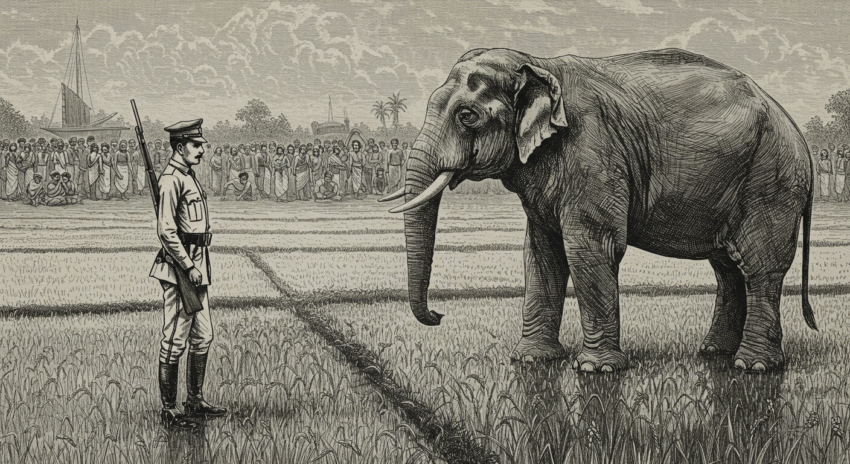

I sent for a better rifle and found the elephant in a paddy field, calmly eating. It wasn’t dangerous anymore, but a huge crowd followed me, expecting me to shoot. I didn’t want to—it was like destroying a valuable machine—but their excitement trapped me. A white man in the East has to play the part of a sahib, or they’ll laugh. I had to shoot.

I fired three times. The elephant collapsed, suffering but not dying. Its pained breaths haunted me. I fired more, but it didn’t stop. I left, unable to watch. Later, I heard it took half an hour to die, and the locals stripped it bare.

Some said I was right; others said it was wrong to kill an elephant over a coolie. Legally, I was covered. But I knew I’d shot it to avoid looking like a fool.